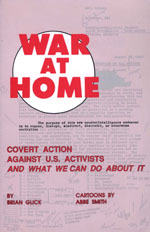

War At Home: Covert Action Against U.S. Activists And What We Can Do About It

War At Home: Covert Action Against U.S. Activists And What We Can Do About It (1989, Boston, MA.)

During the advent of illegal animal liberations in the United States the FBI had very little in the way of actionable intelligence on those responsible. That all changed when a mentally ill-former activist with a history of violence and stalking began speaking with the Bureau. His name was Bill Ferguson, and while he is best known as the activist who shot Last Chance for Animals founder Chris DeRose in the back, his legacy as the first North American super snitch is far more obscure. Once he began cooperating grand juries sprung up all over the country, homes were raided, and the dirty tricks experienced by other movements began entering the militant vegan arena. In response many grassroots animal organizations began to distribute Brian Glick’s excellent booklet, War At Home.

Clocking in at under 100 pages, War at Home covers all of the most important moments in the FBI’s Counter-Intelligence program, (Better known as COINTELPRO) including the events which occurred after COINTELPRO was supposedly shut down. In plain language and with surprising detail Glick discusses the means and aims of the FBI’s attempts at ending domestic dissent. More than a must read on past abuses, War At Home is also an invaluable handbook on security culture and support for those targeted by law enforcement harassment campaigns. The current wave of crackdowns on the Occupy movement make the free distribution of this booklet more important than ever- please share it with your friends.

|

||